Two major rivers intersect in the City of Des Moines, posing a flood risk to residents and infrastructure. Barr helped enhance flood resiliency by bringing levee systems into compliance with detailed design and construction project management.

Two major rivers intersect in the City of Des Moines, posing a flood risk to residents and infrastructure. Barr helped enhance flood resiliency by bringing levee systems into compliance with detailed design and construction project management.

How Iowa’s capital is meeting the challenge of rising rivers

Around 1900, “Des Moines Does Things” was selected as a city slogan to celebrate the city’s prosperity and “can-do” spirit, according to Iowa’s newspaper of record, the Des Moines Register. In the late 2010s, Des Moines again showed a bias toward action as the city recognized the need to proactively address rising river levels and more frequent extreme weather events.

As towns and cities across North America come to terms with a future that portends more frequent flooding and severe weather events, communities can learn from one another. In addition to Des Moines, cities like Minot, North Dakota, Fargo-Moorhead, and others across the Midwest are working to build the resilient flood-risk-management systems that can help them thrive in more uncertain times.

Des Moines addresses a new reality

The Des Moines and Racoon rivers merge a few blocks south of the city center. The city traces its origins to this confluence, which frequently attracts the attention of the city’s public works and engineering staff due to its susceptibility to flooding.

Aging infrastructure, changing weather patterns, and our better understanding of hydrology are culminating to reveal a troubling reality: Many levee systems across the country may not be tall enough.

Recent flow-stage frequency analyses revealed that Des Moines’ elaborate levee system, constructed in the early 1970s, may not provide sufficient protection from the types of water levels expected in the coming years. This scenario plays out in virtually every city that grew out from a major river connection. Aging infrastructure, changing weather patterns, and our better understanding of hydrology are culminating to reveal a troubling reality: Many levee systems across the country may not be tall enough.

Recognizing these vulnerabilities, Des Moines partnered with the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE), FEMA, and a team of consultants to target and upgrade sections most at risk. This forward-looking investment will not only reinforce the city’s ability to safeguard people and infrastructure, but also preserve its FEMA levee accreditation, the federal designation that frees property owners from the requirement of purchasing flood insurance.

“If you wait for levees to overtop or fail, then you’ve got all of the cleanup and restoration that you have to do, plus you have to upgrade your levee system,” said Joe Waln, a senior water resources engineer at Barr who served as hydraulics engineer for Barr’s role in designing three phases of levee upgrades in the downtown area of Des Moines. “But if you can find the funding and the political will to upgrade levee systems proactively, you have a better chance of avoiding those disasters that we see in the news.”

Levee system upgrades are often the most logical path for cities confronting aging systems and more intense storm events. Yet, the process can be complex, time-consuming, and costly if not approached strategically. Planning involves studies of local hydrology, river hydraulics, and geotechnical conditions. Success depends on understanding the community’s tolerance for risk, evaluating design tradeoffs, navigating regulatory requirements such as the USACE’s Section 408 if construction of the existing system involved federal funding, and leveraging funding opportunities while never losing sight of public safety.

Here’s how cities like Des Moines are making wise decisions about their levee system upgrades.

They target the most critical issues

An interesting shift in recent years has been the USACE’s transition from a pre-defined design assessment (i.e., specific criteria) toward a risk-assessment-based framework.

A deterministic assessment uses fixed, single values for parameters and assumes one definite outcome, ignoring probability and uncertainty. In contrast, a risk assessment (often a quantitative, probabilistic assessment) is a systematic approach that identifies hazards, assesses potential consequences and their likelihood, and characterizes risk by explicitly accounting for uncertainty in variables.

Risk assessments offer a more comprehensive understanding of potential outcomes by incorporating statistical distributions of data. This leads to more informed and nuanced decision-making, especially for complex levee systems.

While deterministic methods provide straightforward, easily interpretable results, risk assessments offer a more comprehensive understanding of potential outcomes by incorporating statistical distributions of data. This leads to more informed and nuanced decision-making, especially for complex levee systems.

In Des Moines, the City started with a deterministic approach, designing the first three phases of levee upgrades to align with FEMA accreditation criteria. As inflation drove up construction costs, the City pivoted to a risk-based design approach for the remaining phases to maximize flood risk mitigation while efficiently using public funding resources.

“Funding these projects is a huge challenge for any city, and designing for every imaginable flood scenario would cost more than anyone can afford,” says Mark Kretschmer, a senior civil engineer who served as project manager and engineer of record for our design work in Des Moines. “The City of Des Moines took the risk-assessment approach and said, ‘Let’s identify where the critical issues are within our levee system and put our money where it matters most.’”

Targeting high-risk levee sections through a semi-quantitative risk assessment (SQRA) with the USACE and the project consulting team helped mitigate escalating project costs, an approach that potentially will save the City significant expense. Because the process is a joint effort between the City and USACE, it can streamline the FEMA accreditation timeline.

They engage the governing agencies early in the process

Some levees involved federal funding for their initial construction or are part of the PL 84-99 program. In this scenario, upgrades trigger specific design requirements under Section 408 of the Rivers and Harbors Act, which governs alterations to federally funded civil works projects. The more complex the upgrade, the more hurdles a Section 408 review can introduce—circumstances Barr has encountered time and again for levee projects. Applicants must demonstrate that proposed modifications will not impair the system’s function, harm the environment, or compromise public safety. The USACE reviews the proposed modifications at design milestones, is engaged during construction, and grants the 408 permission.

A clear understanding of Section 408 is essential, and missteps can add months, if not years, to a project. Early coordination with the USACE, detailed technical documentation, and a strong engineering rationale all help streamline the process and avoid delays.

They mitigate geotechnical risks

A good consultant will tailor a team to suit a project’s needs. For levee upgrades, geotechnical engineers and hydrologic and hydraulic (H&H) engineers always have a seat at the table. That’s because there’s more to it than just building a taller levee. Geotechnical stability, seepage mitigation, and how water interacts with structures are key factors informing design.

“As effective as levees are at blocking the water, the water will try to get through,” Joe Waln said. “Our geotechnical engineers are always part of these projects to assess soil and slope stability and prevent adverse seepage conditions.”

Geotechnical experts investigate subsurface conditions and seepage factors. H&H engineers predict how system changes will affect flood stages upstream and downstream. And in urban settings, civil engineers resolve conflicts with utilities, transportation corridors, or other infrastructure. Each of these elements carries cost, risk, and long-term operation and maintenance implications.

They leverage funding sources and stretch their dollars

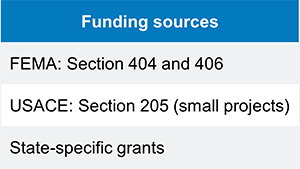

Financing levee upgrades presents its own set of challenges. Fortunately, several federal, state, and local programs exist to help offset costs. For example, FEMA’s Hazard Mitigation Grant Program (Section 404) helps fund some projects that reduce future disaster risk. To access these funds, applicants must complete a rigorous cost-benefit analysis.

By gathering and analyzing technical data—ranging from projected flood damages to long-term maintenance costs—we help clients build their case for investment, giving communities access to resources that make critical projects financially feasible.

Once communities have leveraged funding sources, they naturally want to find ways to make those dollars go far. Value engineering finds smart, cost-effective ways to meet safety goals without overdesigning or overspending.

Levee upgrades involve many moving parts: structural elements, pump stations, drainage modifications, and even the operations-and-maintenance manuals that guide long-term performance. There’s a lot to think about at every stage—from the planning and feasibility phases to design and through construction.

Consider pump stations, for example. A necessary component of many levee systems, they help regulate the accumulating storm runoff behind the levee and pump it into the river as needed.

“Just flipping the switch on a pump station can cost the city plenty of money,” Mark Kretschmer said. “So, how do you operate it most efficiently? What’s the best way to access it so you can maintain and clean it? How do you set up your operations manual?”

Pump stations are just one component of a large levee system. But asking probing questions about all aspects can help cities efficiently navigate a complex and unfamiliar process.

Think boldly, start sensibly

Start with steps that open the door to a bigger conversation—one focused on long-term preparedness and resiliency.

As with many large undertakings, the first step in a levee upgrade can be the most difficult. The key is to start with steps that open the door to a bigger conversation—one focused on long-term preparedness and resiliency.

“The first thing that comes to mind is having that value engineering conversation very early on and making the investment in the semi-quantitative risk analysis,” Joe said. “That is your biggest opportunity to realize savings.”

Equally important is choosing the right partner. Look for a consultant who combines deep technical expertise across multiple disciplines with the flexibility to tackle projects of all sizes. Just as critical, seek out a team that prioritizes personalized service—one that will listen, adapt, and help make informed, confident decisions that are right for your city.

Is your community’s levee system at risk? Barr can help. Contact our flood-risk-management team.

About the authors

Joe Waln, vice president and senior water resources engineer, has more than 20 years of experience in civil and water resources engineering. He has served as project manager and project engineer for public and private clients in both the United States and Canada. His experience also includes scour analysis, dam-breach analysis, watershed BMP studies, FEMA letters of map revision (LOMR), and FEMA accreditation for flood-risk reduction systems.

Mark Kretschmer, vice president and senior civil engineer, specializes in projects related to flood control, hydroelectric, mining, and stormwater management projects. He assists clients with civil engineering design, specifications, permitting, cost estimating, and construction management. Mark has provided design and geotechnical expertise for several of Barr’s large-scale flood risk management efforts and has worked with numerous state and federal agencies.

Image gallery (below)

-

Work along the north bank of the Des Moines River included slope stabilization and riprap improvements to protect the levee from erosion, as well as a clay blanket to minimize seepage.

-

A landslide seepage relief trench was necessary to manage seepage under the levee during flooding events.