Five strategic steps to manage chloride levels in your community’s watershed

Road salt—typically sodium chloride—helps keep winter roads, sidewalks, and parking lots safe, but it can also enter the environment during storage, transport, or application.

Road salt—typically sodium chloride—helps keep winter roads, sidewalks, and parking lots safe, but it can also enter the environment during storage, transport, or application.

Rising chloride levels in watersheds across North America are threatening aquatic ecosystems, compromising drinking water quality, and accelerating infrastructure corrosion. This article outlines five strategic, proactive steps that communities can take to monitor chloride levels, implement source control, engage stakeholders, and adopt innovative practices to protect water quality in their watersheds.

High levels of chloride are toxic to aquatic life, disrupt natural lake mixing, damage infrastructure, and can affect human health.

Communities across the U.S. and Canada are facing a growing challenge: rising chloride levels in local water sources. Whether from road salt, water softeners, or industrial runoff, excess chloride is quietly disrupting freshwater ecosystems, harming plants and aquatic life, degrading soil quality, and increasing water’s corrosivity. The good news? With the right strategies in place, communities can significantly reduce chloride pollution to protect aquatic life, infrastructure, and human health.

How does chloride end up in your watershed?

Chloride is commonly found in nature as a salt, often in rock formations or soil. When it comes into contact with water, it dissolves with the flow, making remediation challenging and costly.

A common source of chloride is road salt (sodium chloride), which is used as a deicer on roadways, sidewalks, and parking lots. Deicers can enter the environment during storage, transport, and application. Chloride is also present in some fertilizers, dust suppressants, industrial processes, and water softening agents.

Step 1. Assess and monitor chloride levels in your watershed

For example, in Minnesota, the chronic standard limits the average chloride concentration to 230 mg/L over a four-day period, while the acute standard sets a maximum one-hour average of 860 mg/L.

Monitoring chloride levels provides valuable information that aids in prevention and mitigation. Monitoring methods include:

-

Continuously measuring chloride levels with conductivity probes for a more accurate assessment of chloride concentrations and source loadings

-

Monitoring chloride levels for each mixed layer in stratified water bodies, by season, to evaluate impacts on mixing status and anoxia

-

Conducting a long-term chloride trend evaluation to distinguish climatic variables from anthropogenic changes

-

Using geographic information system (GIS) technology for water quality management (WQM)

Step 2. Implement source control measures through education

The most effective way to minimize chloride levels is to implement preventive source control measures.

The most effective way to minimize chloride levels is to implement preventive source control measures. Start by engaging the community and policymakers through education on the importance of reducing chloride pollution and encouraging municipalities, businesses, and residents to use less salt on outdoor surfaces. For example, by encouraging the use of brine instead of solid salt and pre-wetting in advance of winter precipitation, salt usage can be reduced by up to 90 percent.

A key component of preventive measures is to provide applicators with training and certification on the proper equipment, efficient timing, methods of salt usage, and equipment calibration to avoid over-application.

Step 3. Engage the community and policymakers

Local governments can create policies that promote smart salting, suggest alternative deicers, and offer incentives for businesses and residents, such as stormwater utility credits, to adopt best practices.

To identify and prioritize the biggest sources of chloride, communities can use GIS to assess land use and land cover—focusing on areas like transportation corridors and parking lots tied to commercial, industrial, institutional, and multifamily residential zones. This crucial information can help guide policy and education initiatives. Based on our extensive experience with chloride source assessments, Barr has developed and enhanced our GIS water quality modeling tool to quantify and map chloride source loadings at a parcel scale and predict downstream impacts on water quality.

Step 4. Implement infiltration practices and alternative impervious surfaces

Infiltration practices are vital tools in managing chloride levels. Communities can prevent high chloride levels by strategically placing infiltration systems to manage runoff and reduce chloride concentrations, and by avoiding snow storage in dedicated infiltration areas.

Heated and permeable pavements also reduce runoff and promote infiltration, eliminating the need for deicers.

Step 5. Treat and mitigate chloride

Are chloride levels still too high in your community? Treatment, mitigation, and prevention options are available. Below, we take a look at one community’s efforts to address chloride pollution in a popular Midwest lake.

Case Study: Parkers Lake

Parkers Lake is a 97-acre lake in Plymouth, Minnesota, within a watershed area spanning 1,065 acres. Its experience with chloride pollution provides useful lessons on the complexity and expense of treating and mitigating chloride once it enters water bodies.

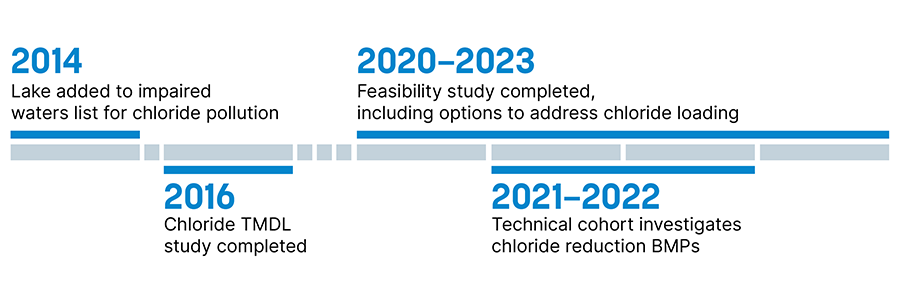

In 2014, Parkers Lake was added to the impaired waters listing for chloride pollution. Two years later, a chloride total maximum daily load (TMDL) study was completed by the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA). In May 2020, the Bassett Creek Watershed Management Commission (BCWMC) completed a feasibility study, including options for addressing chloride loading. Then, in 2021–2022, the City of Plymouth convened a technical cohort to investigate chloride reduction best management practices (BMPs), including in-lake chloride removal.

In November 2023, the BCWMC completed its study to identify viable options for removing chloride and meeting the MPCA standard. The study’s scope included two potential mitigation strategies:

-

Alternative 1—Pump/discharge hypolimnetic water to a sanitary sewer.

-

Alternative 2—Evaluate use of 1) a reverse osmosis (RO) system or 2) an ion exchange (IX) system, to pump/treat hypolimnetic water and return it to the lake.

The study also evaluated lake chloride mass balance, assessed the possibility of delisting, and reported the study results and recommendations. Ultimately, the Metropolitan Council—the permit authority for special sanitary sewer discharges—decided not to permit Alternative 1, and Alternative 2 was not recommended for Parkers Lake as it would be a cost-prohibitive option for meeting the chloride standard. Barr continues to work with BCWMC and other communities to further study source control alternatives and evaluate pumping strategies to manage and reduce chloride levels in other water bodies.

Ready to get started?

Reducing chloride in your community’s watershed will likely require some combination of assessment, source control, community engagement, best management practices, alternative impervious surfaces, and/or treatment. By understanding the sources of chloride, monitoring chloride levels, and implementing effective strategies for the long term, communities can protect their watersheds and promote a healthier environment for all. Contact us for help reducing chloride levels in your community’s watershed.

About the authors

Greg Wilson, senior water resources engineer, has more than three decades of experience in the areas of hydrology and hydraulics, surface water quality, GIS, limnology, and watershed and lake management planning, including 1W1P and Nine Element Plans. He performs watershed and in-lake water quality modeling, recommends management actions, and facilitates technical advisory meetings for development of lake management plans. Greg has conducted water quality and water quantity monitoring and modeling and/or TMDL/WRAPS studies for more than 100 lakes. He also leads design, sediment analysis, chemical dose determination, and/or alternative treatment options for internal phosphorus control in lakes and ponds. Most recently, Greg led the integration of chloride modeling capabilities into Barr’s GIS-based water quality model, improving its ability to identify and prioritize chloride sources at a watershed scale.

Karen Chandler, vice president and senior water resources engineer, has more than three decades of experience working with watershed organizations and cities to develop and implement watershed and stormwater management plans. She also oversees hydrologic, hydraulic, and water-quality analysis and design and the construction of stormwater projects. Karen provides clients with extensive community relations support and assists with public presentations and the facilitation of public processes.